Study Guide

Study Guide

The Odyssey, Books 1-4

Study Guide

Study Guide

The Odyssey, Books 1-4

This study guide has been adapted from one I created for my World Literature class, so it emphasizes the literary characteristics rather strongly. But I thought you might find the change in emphasis rather interesting, and that this background information might add another dimension to your understanding of the epic. The quotations are all based on Robert Fitzgerald's translation.

See also the page of Odyssey links, as these are likely to answer a number of your questions...and possibly questions you didn't even know you had.

| Book 1 | Book 2 | Book 3 | Book 4 |

Book One

Line 1: As with the Iliad, we begin the poem with an invocation, as is typical for an epic poem.

"Homer" is probably not a single person's name, and almost certainly these poems, which are extremely long and were originally meant for oral performance, were composed by many professional bards over many centuries. The word "Homer" means, interestingly enough, "exile" or "hostage." I find it kind of ironic and touching that somebody called "exile" is performing a tale about somebody who wants only to go home.

As you read through all this material about xenia and the xenos, you might want to think about the fact that an exile's very life might depend upon the xenia tradition. No wonder it's emphasized so heavily. As you may recall from our class Zeus page, the xenia tradition was said to come straight from Zeus in his capacity as Zeus Xenios.

The invocation is followed by what is called an argument. The argument of a long poem or a play is a short summary of what is to come. In this poem, the argument extends from line 5 to line 15.

This is actually quite a significant moment, as it's one of the earliest representations in literature of a god with a disinterested motive for helping a human being. The old Mesopotamian gods, such as Enki and Ishtar, were interested only in human beings as potential servants. Athena, on the other hand, loves Odysseus for what he is, not for what he can or might do for her. Some scholars see a sexual dimension in Athena's playful, almost flirtation manner toward Odysseus, but since she is the eternal virgin there is no question of her imitating Aphrodite and having a full-blown affair with a human being.

If you want to review Athena's attributes, see our Athena page.

Second, we see a direct supplication to Zeus, similar to the supplication that Thetis made on behalf of her son, Achilles. Zeus was the protector of petitioners for justice, and is frequently depicted in vase paintings accompanied by Themis, the goddess of justice. Remember that his role as the protector of suppliants was as important as his role as upholder of hospitality to guests.

We see another parallel, but in this case to other works as well as the Iliad, in lines 79-80 when Athena tries to get Zeus over onto her side by asking him "Had you no pleasure in Odysseus' offerings/beside the Argive ships, on Troy's wide seaboard?" It's amazing in how many stories we see a focus on the gods' taste for barbecue. Even Noah makes a "burnt offering" as soon as he emerges from his ark (I always figured that explained what must have happened to the unicorn). The Mesopotamian gods were fond of sacrifices, too; in fact, that's one of the major reasons they allowed human beings to exist.

Of course, the true motive behind sacrifice to a deity is the fact that religious sacrifice is an excellent way of focusing the mind on the divine, and in feeling a sense of closeness to the divine presence. Think about why so many people in our own society practice Lent.

Still, I love Zeus's definition of wisdom in lines 85-86: "There is no mortal half so wise; no mortal gave so much to the lords of the open sky." Zeus knows what he likes! Like the mortals we saw in the Greek camp at Troy, Zeus likes stuff. Agamemnon and Achilles fought over Briseis, but that idea of "he who dies with the most toys wins" is one of the main motivations in both Homeric epics--even among the undying gods.

Honor is very dependent on how much you are given, and in Zeus's case he wants to be given sacrifices. You'll see that craving for gifts again and again throughout the poem. If it weren't for greed, most of the events in this story would never occur. When you get to the section about the cave of the Cyclops, for instance, pay attention to the reason Odysseus gives for wanting to hang around until the Cyclops comes home: he's hoping that he can pick up a few guest gifts as well as the items he and his shipmates have already stolen from the Cyclops' storeroom.

88-96: in medias res

Zeus also explains in great detail to Athena exactly who were the parents of Polyphemus. This is of great importance. Remember that the Heroic Bronze Age was intensely patriarchal and aristocratic, and a person's lineage was a matter of the utmost concern. We saw this in the Iliad, as well, in that scene between Diomedes and Glaucus that Richard mentioned in his Week Ten post. As Richard remarked, it seems strangely out of place in the middle of the war. To the Greeks, however, it would have made perfect sense.

Moral of the story: Unless you are Hermes, don't steal somebody else's cattle!

139-224: Xenia and reverence

Notice also the respect that Telemakhos shows for his absent father. Although Odysseus has been gone for years, Telemakhos keeps him alive in memory. He takes Athena's spear and stores it in "a polished rack/against a pillar where tough spear on spear/of the old soldier, his father, stood in order" (155-157). Even though Telemakhos was only a tiny baby when Odysseus went to war twenty years ago, he treasures his father as a dutiful son should.

Hospitality requires that the guest be fed and made comfortable before the host can ask any questions, but Telemakhos asks as many as he can as soon as he can. This is not only to try to find news of his father, but also to determine what relationship this person has with him. That is, is this somebody who has an established xenos relationship with the family? As you see, Athena makes haste to reassure him by saying "Years back, my family and yours were friends/As Lord Laërtes knows; ask when you see him" (223-224). The reference to Telemakhos's grandfather immediately tells him where he and his guest stand in relation to one another.

344-363: Recognition

364-462: Telemakhos makes a stand

It may have seemed rather shocking to you to hear Telemakhos, who up until this point has seemed so polite and well-mannered, speak so rudely to his mother. And it might have seemed even more shocking to read her meek and obedient response, where she "gazed in wonder and withdrew,/her son's clear wisdom echoing in her mind" (397-398). Wisdom? Did we miss something, or what?

But one has to keep in mind just how patriarchal and male-centered this society was. Telemakhos has spoken as the head of the house, as if he had a right to authority. Even though his harsh words were directed at her, she now has reason to think that maybe, just maybe, he will grow up in time to get them out of this mess. Telemakhos's youth has been an outright danger to both of them, as nobody respects him. This becomes blatantly obvious in Book II, when he announces his impending departure and the suitors behave in a most disrespectful manner, and then again in Book IV, when the suitors start plotting to kill him.

In an on-line essay, Mary deForest of the University of Colorado compares Telemakhos to the ephebe, or young man engaged in ancient Greek initiation rites:

Telemachus of the Odyssey is the perfect example of an ephebe. He set off from home, young and inexperienced in the ways of the great world. When he returned to Ithaca with news of his father and presents from his father's friends, he possessed a beard. Its existence (mentioned first at Od. 18.173–74) gave Penelope the excuse to trick the invaders of her house. Odysseus, she claimed, had instructed her that, if he did not return, she should wait until Telemachus grew a beard, and then marry again (18.269–70). To get gifts from her suitors, she promised to consider remarriage. By Book 18, clearly, Telemachus had a beard. The logic of hair growth implies that he had one all along. The logic of narrative insists that Telemachus' beard was somehow jump-started by his experiences in the larger world.Like Telemachus, the ideal ephebe left the security of home. The Athenian ephebes guarded the borders and were drilled in their military exercises. During this two-year period, they were viewed as belonging to an age-group, helicia. They were identified by their tribe, a classification dominated every aspect of Athenian civic life--legal, political, religious, and military. At this unique period of their lives, ephebes lived outside the polis in the wilderness, together as young men.

In the same way, Telemakhos will assert his newfound grown-up authority with Eurykleia, the old nurse, in Book II. When she asks him, rather indulgently, "Dear child, whatever put this in your head?" (381), Telemakhos replies "There's a god behind this plan" (390). Then he makes her promise not to tell his mother "until the eleventh day, or twelfth, or till she misses me, or hears that I am gone" (391-393). He thinks she might not notice he's gone for eleven days? Does this remind you of certain behavior on the part of college students who leave home for the first time? Telemakhos, call your Mom!

|

Lines 1-7: Bardic repetition

Antinoös boasts that "one of her maids, who knew the secret, told us" (114). You'll also be happy to know that when Odysseus gets back he's going to pick off the faithless maids who consorted with the suitors.

Struck by the fact that Odysseus's wife does not behave in the gentle, submissive way that would be expected of a Greek lady (Greek ladies, and Roman ladies in later years, were classified with minors when it came to legal rights for their entire lives, dependent upon either a male relative or a husband to make decisions for them), Antinoös tries to get Telemakhos, who is the man of the house and is now finally acting like it, to make a decision: "dismiss your mother from the house, or make her marry/the man her father names and she prefers" (119-120). Yes, he really does mean Penelope's father--this is not some kind of elaborate metaphor. Because she cannot speak for herself, she would be legally bound to obey either her son (head of the house) or her father. What the suitors propose is that she be sent home to be married out of her father's house, as if she were a teenager.

Antinoös also threatens that Penelope "may rely too long on Athena's gifts--/talent in handicraft and a clever mind" (122-123). Athena was the goddess of cleverness of mind and cleverness of hands, so she was traditionally associated with weaving. He says, half admiringly, "Wits like Penelope's never were before" (127), almost a direct echo of Zeus's admiring words about Penelope's husband. How, then, after being married to an Odysseus, could a woman like Penelope even tolerate a union with a dumb lout like Antinoös?

Athena disguises herself as Mentor not once but twice in this epic. She seems to recognize his worth.

She gets a good return on her investment. The pious son of Odysseus makes a libation to the gods before the ship even gets out of harbor, and "most of all to the grey-eyed daughter of Zeus" (452), that is, to Athena herself. No, he is not "sucking up." She's still in disguise, remember?

|

I know I didn't assign this book, but would you mind taking a quick look at the first twelve lines? Then we'll move on to Menelaus and Helen.

Lines 1-12: Arrival at Pylos

Telemakhos's family has a solid xenos relationship with Nestor's family, strengthened by Nestor's ten years in the field with Odysseus at Troy. And when Telemakhos leaves Pylos to visit another family xenos, King Menelaos of Sparta, he takes a companion with him: Nestor's son.

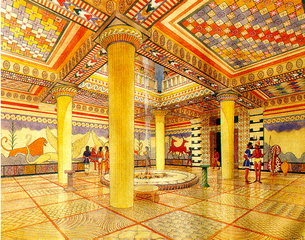

I love Book IV, just because I think it's so terribly funny. Here's Helen, the cause of all the trouble at Troy, living the high life with her complacent cuckolded husband, surrounded by the spoils of Troy and the proceeds of what appears to have been the ultimate xenia tour of Egypt. They've got guest gifts and loot piled up in every corner of their place. If it is true that the one who dies with the most toys is the winner, I'd say Menelaos and Helen are definitely the frontrunners here. All that, and the prospect of the Elysian fields, too!

32-37: The reason behind xenia

This part of the poem reminds me forcibly of the scene in Paris's bedchamber where Hector tries to get Paris to stop polishing his armor and get out on the front, but Paris seems to think he can talk his way back into honor. And just like in that scene, Helen comes in and starts putting herself down, as if calling herself names will make everything okay. She recognizes Telemakhos from his resemblance to his father, and she knows that he knows that she's ultimately responsible for the fact that Odysseus is still missing. Helen is no fool; she even saw through the Trojan Horse trick and almost overset it, as we'll see when we get to the Aeneid. She remarks,

This boy must be the son of Odysseus,

Telemakhos, the child he left at home

that year the Akhaian host made war on Troy--

daring all for the wanton that I was. (150-153)

It seems to me we've heard this speech before, or at least Hector did, back at Troy.

In this scene, Helen comes off as the perfect, contented housewife. But although she does exactly what a housewife should, concerning herself with the womanly duties of preparing wool to weave into cloth (the duties that Andromache abandoned to stand on the walls of Troy and watch for weak spots in the Trojan defenses), her wool is kept in a silver basket with a hammered gold rim and her distaff, the staff onto which the wool is wound, is fashioned out of gold. The wool itself is purple. Purple dye was incredibly expensive, as it could only be attained with great effort from a rare shellfish found near the African city of Tyre. Martha Stewart never had household accessories like Helen's.

And where can we buy some of that anodyne stuff she pulls out in line 232?

At this point, Menelaos takes a digression to tell a tale in which he, too, comes off as pretty wily. You'll notice that within the narrative there are a lot of pauses where people tell long tales. It's a function of the in medias res style. Although Menelaos returned home to Sparta long ago, we get to hear something about his adventures after the fact. We'll receive most of Odysseus's adventures in the same way, as he recounts them to the friendly Phaiakians who take him in when he lands on their shores.

Menelaos's story also, of course, serves the purpose of foreshadowing Odysseus's successful homecoming.

|

Telemakhos's modesty and lack of greed prove that he's well brought up, and Menelaos is impressed with his good manners in turning down the excessive amount of stuff he's just been offered. So instead, he offers Telemakhos something that is smaller but is even more precious: a wine bowl made by Hephaestus himself. It pays to know the rules of polite behavior!

Test your knowledge (or just take some wild guesses...) and play the on-line interactive Odyssey Game. You can choose to be Odysseus himself, Penelope, or Telemakhos, and navigate your way to a happy ending. Even when you make the wrong choices, you always get another chance and you will always be told why your choice was wrong. The set-up is technically simpler than that of the Iliad game, so even if you had trouble with the interface of that one you should have no trouble with this one.